The Reuters news staff had no role in the production of this content. It was created by Reuters Plus, the brand marketing studio of Reuters.

PRODUCED BY REUTERS PLUS FOR

With quantum computing breakthroughs, advanced packaging leadership, and a €43 billion EU Act in play, Ireland’s microelectronics ecosystem is shaping the future of tech around the world.

Disclaimer: The Reuters news staff had no role in the production of this content. It was created by Reuters Plus, the brand marketing studio of Reuters. To work with Reuters Plus, contact us here.

Invest in Ireland

With skilled talent, supportive incentives and a stable economy,�Ireland is the perfect platform for world-leading companies to scale and grow.

Find out how to Invest in Ireland here.

Silicon island:

How Ireland became a semiconductor powerhouse

EN

JP

CHOOSE LANGUAGE:

They call it Silicon Island. For half a century, a small country at the western extremity of Europe has been building deep expertise in the chips industry and today it is making the discoveries that will shape the semiconductors sector for generations to come.

There are good reasons why Ireland has become home to 15 of the world’s top 30 semiconductor companies. Its rich microelectronics ecosystem is based on firm foundations. R&D hubs of world-leading private companies work side-by-side with innovative start-ups and government-backed research institutes, creating an environment of exceptional collaboration and support.

The future of semiconductors

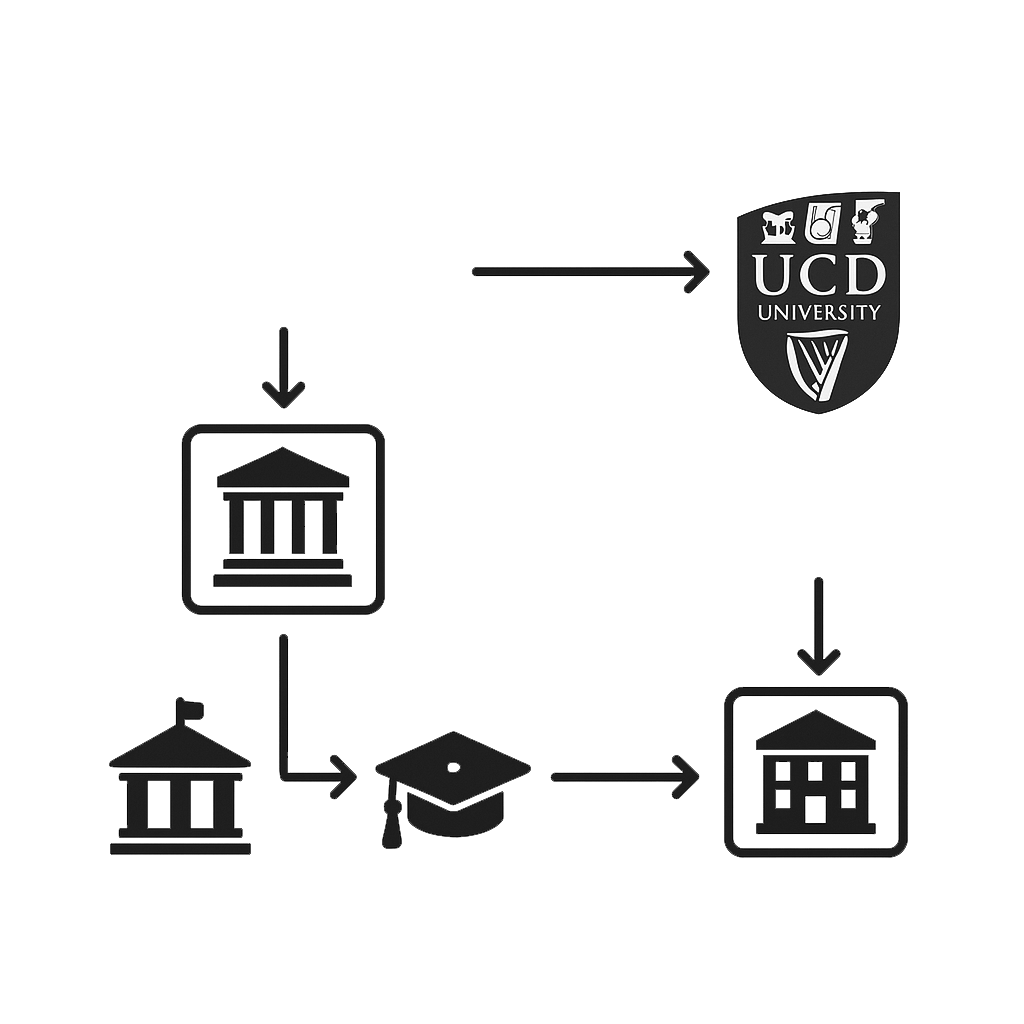

Jason Lynch is a prime example of Ireland’s semiconductor ecosystem in action. After working at ADI’s Irish operation he moved into the adjacent start-up world and became CEO of Equal1, a quantum computing spin-off from University College Dublin. In March, at the APS Global Physics Summit in California, Equal1 made the world sit up when it unveiled the Bell-1, a revolutionary system that integrates the elements of a quantum computer into a single silicon chip.

�The Bell-1, rack-mounted and easily deployable in existing data centers, is the world’s first quantum computing server based on the existing semiconductor technology used to power modern microchips. Lynch says this “paradigm shift” was enabled by the intimate ecology of Ireland’s semiconductor sector, where experimentation takes place in alignment with the needs of business. “Ireland is a great place for that because there are senior teams here looking at the architecture that’s going to be needed. We have the ability to engage with them and tell them what we’re doing,” he says.

�The breakthrough highlighted Ireland’s reputation as a global leader in chip technology. It will also inject added impetus into Ireland’s rapidly expanding semiconductor sector. “Quantum computing will be the next wave of growth for the semiconductor industry here in Ireland,” says Lynch. “Ireland is a small enough community that we can get together and do something meaningful with impact on the global stage.”

A nation of engineers

Ireland’s hub position in the global supply chain for semiconductors is a consequence of its far-sightedness in public education and the emergence of an abundant tech talent pool. It boasts the highest level of STEM graduates per capita in the European Union among 20-29-year-olds, and engineering has long been valued in the curriculum “When we were in school engineering was considered the top job to get,” recalls Prof. Peter O’Brien, head of advanced packaging research at Tyndall National Institute, Ireland’s leading deep-tech research center. “There was a very strong push towards engineering and the education system was a big part of that.

O’Brien first arrived at Tyndall (then called the National Microelectronics Research Centre, or NMRC) in 1990 and found himself alongside talented Irish colleagues who have risen to senior roles in the semiconductor industry, such as Ann Kelleher, who became global head of technology development at Intel, which located in Ireland in 1989. O’Brien and many of his engineering cohort went to work in America’s semiconductor industry, then brought their skillsets home. He developed a specialism in photonic semiconductors and today is Tyndall’s head of advanced packaging research.

�The institute’s pivotal role in the semiconductor sector epitomizes Ireland’s Silicon Island strategy where government, industry and academia work in close partnership. “We do a lot of applied industrial research, especially in semiconductors,” says O’Brien. “My team are developing working prototypes with companies. We make things and then look at scaling them up. That is very attractive to industry.” Irish ministers are highly engaged in the sector. “We see them regularly,” says O’Brien. “They can quickly find out what is going on and that really helps move things quickly."

Ireland to the world

Silicon Island is also a product of Ireland’s outward-facing and welcoming national culture. The nation’s geography has long obliged it to look overseas, westwards to the United States and eastwards to Europe and to Asia.

�Historic links to America, including family connections and shared language, have underpinned its growth in semiconductors. Talent has flowed in both directions, building strong personal networks and attracting companies such as AMD and Qualcomm to Silicon Island. Ireland has developed an intuitive grasp of the quirks of the semiconductor industry and its 18-month work cycle.

�O’Brien is also a visiting professor at Keio University in Japan, which operates a student exchange program with Tyndall. He has hosted numerous Asian companies that seek to introduce their materials to the semiconductor sector. “We can make demonstrators to showcase their technology and prove that it works and get it into the supply chain.”

�Numerous Japanese companies have already taken a stake in Ireland’s semiconductor ecosystem. Dublin’s Magnetic Solutions was bought by the Japanese electronics and semiconductor company Tokyo Electron Ltd. ROHM Semiconductors, based in Kyoto, Japan, acquired the Irish chip firm Powervation, part of Cork’s semiconductor cluster. Nikon Precision Europe, based in Kildare, and Japanese-owned Pentagon Technologies Inc, in Dundalk, provide products and services to the semiconductor industry.

�Ireland is always looking beyond its shores and wants them to come. “We are small and we have no other choice than to get off the island and reach out” says O’Brien. “That’s the way we work.”

IRELAND'S INNOVATION ECHOSYSTEM

Government

Academia

K-NIBRT

South Korea

NIBRT

University

College

Dublin

JAPAN-IRELAND

BUSINESS RELATIONS

1973

Embassy of Japan opens

8000

Employees

44

Japaneese companies present in Ireland

County Kerry

Gallway

Dublin

Something about

Ireland's

Global

Business

Connections

Asian Investment in Ireland

Talent & Workforce

€15.5bn

in annual revenue

leading global biopharmaceutical companies

13 out of 15

Highest STEM Graduates Per Capita

Silicon Island

The process began back in 1976, when Analog Devices Inc. (ADI) chose Limerick for its European headquarters

— Seamus Carroll, VP Semiconductor Unit at IDA Ireland

Advanced packaging is something we have a head-start on, and I would say we are global leaders in that space.

— Peter O'Brien, Head of Research,

Photonics Packaging & Systems Integration, Tyndall National Institute

Semiconductor industry

20,000

Employees

The Bell-1, rack-mounted and easily deployable in existing data centers, is the world’s first quantum computing server based on the existing semiconductor technology

The Bell-1

€400m

PIXEurope Project

His team is working on the €400 million PIXEurope pilot line for photogenic chips, funded through the European Chips Act. With traditional monolithic chips becoming increasingly complex and growing in size, Ireland is leading the world in advanced packaging of smaller integrated circuits - called chiplets - that work in combination in a single unit, he says. “Advanced packaging is something we have a head-start on, and I would say we are global leaders in that space.”

�Chiplet technology is enabling the growth of AI and O’Brien’s team finds itself working at a “sweet spot” where research meets industrial production. “We have about 20 European projects, all in advanced packaging,” he says. “We cannot keep up with the level of interest in this area - we are hiring more people and the opportunities are enormous.”

“The process began back in 1976, when Analog Devices Inc. (ADI) chose Limerick for its European headquarters,” says Seamus Carroll, VP Semiconductor Unit at IDA Ireland. “Since then, a succession of global semiconductor companies from the US, Europe and, increasingly, Asia have decided to locate here in Ireland, identifying it as a gateway to European and global markets. Because of their continued investment and expansion, Ireland’s semiconductor sector now employs 20,000 people and generates €15.5 billion in annual revenue.

This means that Ireland is optimally placed to benefit from the €43 billion commitment created by the European Chips Act, passed by the European Commission after both the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical tensions exposed weaknesses in the global supply chain for semiconductors.

The Reuters news staff had no role in the production of this content. �It was created by Reuters Plus, the brand marketing studio of Reuters.

Produced by Reuters Plus for

Invest in Ireland

Find out how to Invest in Ireland here.

Fast-growing economies, with stable governance, and supportive incentives for investment, attract the world's most exciting companies and investors. Ireland has these in abundance.

Disclaimer: The Reuters news staff had no role in the production of this content.

It was created by Reuters Plus, the brand marketing studio of Reuters.

To work with Reuters Plus, contact us here.

EN

JP

CHOOSE LANGUAGE: